Prices are supposed to change in a free market economy. Things, people, land, money, everything is supposed to go up and down to signal scarcity or abundance. Price changes create an income effect and a substitution effect for consumers. For investors, price changes are a signal for allocating capital. This isn't just theory. The communist economies eventually failed because of prices set by fiat rather than supply and demand.

A key to effective price signalling, however, is that prices are expected to move in both directions. Therein lies the difference between a change in price and inflation. Inflation is about seeing a price go up and then expecting the price to keep going up along with the price of everything else. The signals are more difficult to discern. In the 70s, consumption and investment decisions were driven by expectations that prices will be higher tomorrow. The cost and, yes, even benefits of that period are still with us. Volcker, knowing this was no way to run an economy, kick-started the disinflationary monetary policy that Greenspan continued. It eventually squeezed inflation expectations out of the system. This is one genie the Fed wants to keep in the bottle.

Here it is in Fedspeak, direct from

Kohn's speech last week to the Money Marketeers (the boldface is mine):

"When we try to model energy pass-through econometrically, the results indicate that a break occurred in pricing patterns in the early 1980s: Pass-through is clearly evident before 1980 but it is difficult to find thereafter. I suspect this pattern has something to do with the monetary policy reaction to those shocks and its effect on inflation expectations. In the 1970s, monetary policy not only accommodated the initial shocks but also allowed second-round effects to become embedded in more persistent increases in inflation. Since the early 1980s, the pass-through to core prices has been limited or non-existent, at least in part because households and firms have expected the Federal Reserve to counter any lasting inflationary impulse that they might produce. This result reinforces the need today to keep inflation expectations well anchored."

Kohn is absolutely right in his assessment, though I suspect my view on this matters not at all to the Vice Chairman. The positive outlook on inflation, as per everyone's comments these past two weeks, comes from the abating price increases and even declines in the costs for energy and shelter. But, and there is always a but, Kohn sheds a bit of light on why the Fed remains concerned about inflation, beyond the required rhetoric. From the same speech (the boldface is once again mine):

"In sum, I think that the odds favor a gradual reduction in core inflation over the next year or so, but the risks around this outlook do not seem symmetric to me: Important upside risks to the outlook for inflation warrant continued vigilance on the part of the central bank. I say that not only because of the questions about underlying labor costs and about the future direction of energy and shelter prices but also because our understanding of the inflation process is limited, and I cannot rule out the possibility that the upward movement earlier this year reflected a more persistent impulse that I cannot now identify".

Where did this come from? Perhaps from the mountain of liquidity behind this expansion that helped to prevent a deflation that, thankfully, never arrived.

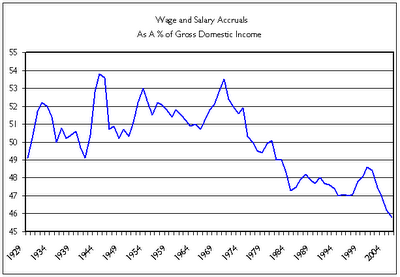

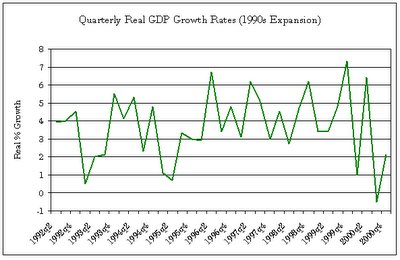

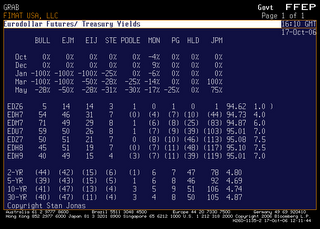

This first chart compares nominal GDP growth to the Fed funds rate as we came out of the 1990-91 recession.

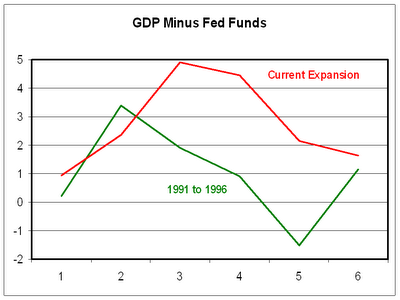

Here is what they did this time around.

This chart compares the difference between GDP and Fed funds for each period. The higher the line, the easier the Fed.

To be fair, enough differences separate the periods to create different policy responses. This time around deflation was perceived as the credible risk to be tackled. Then, inflation was still the big risk and we did not yet full understand that the economy could grow faster without inflation because of technology and globalization.

There is one more difference. In the 90s, the Federal budget deficit was shrinking. Now it isn't. Then, alot was done beginning with Gramm-Rudman in 86 to put the structural deficit into balance. This time, the structural deficit is back.

Another difference? Japan wasn't growing and neither were China or India. As a consequence, the global demand for oil was not expanding as rapidly.

Enough caveats.

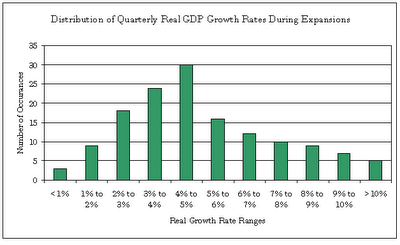

PCE year-over-year averaged around 2.3% during this period in the 90s and ran from 2.9% at the beginning to 1.8% by the end of 1996. This time, the average is the same and we are running at about the same pace, 2.3%, as when the recovery started (of course there was that scary dip in the middle).

So far so good. But lets take a look at the GDP deflator year-over-year, which includes energy and food and all the other non-core items that impact income and wage demands. In the 90s expansion, a 2.1% average and the pace dropped from 2.3% to 1.9%. This time, a 2.7% average and the pace has risen from 2.1% to 3.3%.

Uh-oh.

So Kohn is telling it like it is. They are hoping that a slowdown with rates at neutral and with its hard-won credibility, the Fed can get inflation down before it spills into the core. They have reason to be positive, and cause for concern.

No way to know now how it will turn out, as Poole keeps telling us. But there is more worry than they are letting on. After all, why else is Bernanke has recently been fronting a more open stance against the structural deficit in the Federal budget? Coincidence?